(publishing in the Wall Street Journal)

The mystery of the source of the Nile is almost as old as recorded history—”It would be easier to find the source of the Nile,” Romans said of a futile task. The puzzle was not simply “where” but “how.” How could such a vast river flow 1,200 miles through the driest desert in the world without a single tributary to replenish it? There were many obstacles to discovering the source, from tropical diseases, through local conflicts exacerbated by the slave trade, to geographical barriers, including river cataracts and rainy seasons that turned land into swamps.

The mystery of the source of the Nile is almost as old as recorded history—”It would be easier to find the source of the Nile,” Romans said of a futile task. The puzzle was not simply “where” but “how.” How could such a vast river flow 1,200 miles through the driest desert in the world without a single tributary to replenish it? There were many obstacles to discovering the source, from tropical diseases, through local conflicts exacerbated by the slave trade, to geographical barriers, including river cataracts and rainy seasons that turned land into swamps.

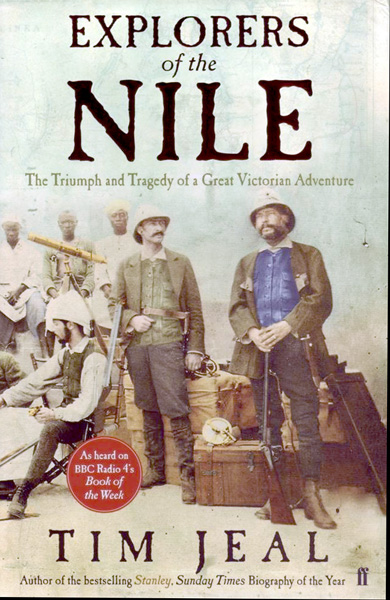

“Explorers of the Nile,” Tim Jeal’s engaging biographical study of the 19th-century adventurers who dared—clamored, even—to face these dangers does not stint on the brutal deaths met by many of them: Mungo Park probably drowned, Richard Lander was shot, the Dutchwoman Alexine Tinné was hacked to death, the French naval officer M. Maizan was mutilated, then beheaded. Yet reports of these grim ends seemed, if anything, a spur to other explorers, and Mr. Jeal examines the reasons, both spoken and unspoken, behind this lust for discovery.

Financial gain and political ends, both of which came to dominate later Western involvement in Africa, played little part: The search for the headwaters of the Nile began in 1856, a decade before the discovery of the diamond mines and gold fields of Africa. Instead, Mr. Jeal identifies personal reasons—a desire to escape routine, existential wanderlust, personal reinvention—and more idealistic ones: to benefit humanity, particularly by eradicating the slave trade; to bring trade to Africa; to extend the empire. There was also the simple human desire to be first.

In 1853, Richard Burton, an army officer, linguist, travel writer and self-promoter extraordinaire, boasted of being the first non-Muslim to visit Mecca, having made the hajj that year. (In fact, at least half a dozen had done so previously.) He was soon looking for new adventures. In 1841, the Ottoman governor of Egypt had sent boats as far as Gondokoro (now Ismailia, in Egypt) to map the reaches of the Upper Nile. Burton planned to search for the source in the lakes of east Africa, then head north to Gondokoro.

The companion he chose for the expedition could not have been more of a contrast to the dark, melodramatic, wordy Burton. John Hanning Speke, an army officer who had served in the Anglo-Sikh Wars of the 1840s, was fair, reserved and careful. He liked the Africans he met and mixed with; Burton despised them, finding company among Arab slavers. They fell out before the voyage even began.

Nevertheless they set out in the summer of 1857 and reached Lake Tanganyika eight months later. Burton had failed to buy enough trading goods or to hire enough porters to carry their gear, which included tents, camp beds, chairs, food, cigars, books and a table—not to mention their scientific instruments, which were so fragile they needed to be swaddled. Because of the porterage problems, they had to abandon their boat along the way and could only look on from the shore. Nonetheless, Burton decided that Tanganyika was the source of the Nile. Having heard of a further lake to the north, Speke traveled on, leaving the desperately ill Burton behind, and found what he named Lake Victoria (Nyanza). He was unable to circumnavigate the water due to political instability, but he was certain that this was the Nile’s source, a contention that Burton hotly rejected.

Nevertheless they set out in the summer of 1857 and reached Lake Tanganyika eight months later. Burton had failed to buy enough trading goods or to hire enough porters to carry their gear, which included tents, camp beds, chairs, food, cigars, books and a table—not to mention their scientific instruments, which were so fragile they needed to be swaddled. Because of the porterage problems, they had to abandon their boat along the way and could only look on from the shore. Nonetheless, Burton decided that Tanganyika was the source of the Nile. Having heard of a further lake to the north, Speke traveled on, leaving the desperately ill Burton behind, and found what he named Lake Victoria (Nyanza). He was unable to circumnavigate the water due to political instability, but he was certain that this was the Nile’s source, a contention that Burton hotly rejected.

A feud was born, with politicking and malice replacing geography and exploration. In the subsequent decades of claims and counter-claims, Burton suggested that Speke had had sunstroke, which “seemed permanently to affect his brain.” In fact, the latter had done all the mapping once their chronometers broke, calculating longitude by using lunar distances (no easy feat), while Burton was so ill that he had to be carried on a litter for most of the trip. In 1864, back in England, Speke died in a hunting accident—Mr. Jeal firmly repudiates Burton’s opportunistic suggestion of suicide—leaving the debate to Burton and his ready pen.

Speke was, as it turned out, correct about Nyanza, and Mr. Jeal is his ardent supporter. Nothing the wily Burton did was, in Mr. Jeal’s eyes, honest or aboveboard; Speke, by contrast, could do no wrong. Mr. Jeal makes an almost unanswerable case, but his stridency makes the reader wary.

Although “Explorers of the Nile” covers the rest of the century, Mr. Jeal’s heart is obviously with these early explorers, who are given disproportionate space. Of his love and admiration for David Livingstone, too, there can be no gainsaying. After Speke and Burton returned with conflicting accounts, Livingstone was sent in 1865 by the Royal Geographical Society to attempt to settle the matter. Livingstone, a missionary, also felt his journey had a higher purpose: to end the East African slave trade. If he could find the river’s source, he hoped, the possibility of new trade routes might create the political will to blockade the ports and destroy the evil trade. Only commerce, with ease of access to food and other goods, could improve health; monogamy and perhaps even Christianity might follow, he thought.

Mr. Jeal is similarly generous to the demons that drove Henry Morton Stanley and puts his search for, and hero-worship of, Livingstone in context, making his famous staged meeting, “resplendent in pith helmet and white flannels,” mounted on a stallion, with the Stars and Stripes flying, touching and admirable rather than vainglorious.

Mr. Jeal’s account of other explorers is more cursory, and the details can seem to flash by for those without previous knowledge of their stories. Samuel Baker and Florence, his Hungarian almost-wife, whom he had purchased in a slave auction on the Danube, met Burton and Speke when they reached Gondokoro. In a spirit of collegiality, Speke gave them his notes, and the Bakers continued on to map the lake Luta N’zigé, which they named after Prince Albert. In 1871, however, Baker claimed Gondokoro for the khedive of Egypt, and this gesture set off what became known as the “Scramble for Africa,” with the European powers vying for resource-rich lands.

It is Mr. Jeal’s contention that the earlier explorers opened the way for this political grab, and thus the sorrows of the 20th century—the war in Sudan, the division of Uganda—can all be traced back to these geographical quests. While this thesis has some validity, the biographical structure the author has chosen does not lend itself to what is ultimately a matter of nation-states rather than individual quests—history, not biography. Once the scramble began, European realpolitik predicated spheres of influence, and the explorers in the field became a mere sideshow, but in Mr. Jeal’s account they carry more weight than their roles can bear.

Because of Mr. Jeal’s prioritizing of people over events, his tale frequently presents the cart before the horse: We open with Livingstone’s journey to confirm Speke and Burton’s findings, only to dart back several decades. And the author, steeped in his subject, is perhaps more hardened to atrocities than his readers are likely to be: When Maizan is mutilated and beheaded, Mr. Jeal merely comments that this was an indication that the trip “was unlikely to be problem-free.” Indeed.

These matters are, however, more than counterbalanced by the author’s command of detail and astute reading of the evidence. There are also wonderful scenes, and asides, that conform to every stereotype one has of British explorers, such as Livingstone’s understatement when confronted by evidence that one tribe practiced cannibalism: “Not ostentatiously so,” he demurred. Or Burton’s first choice of companion for his Nile exploration, a man named Stocks, described by a friend as “an excellent chap, but a mad bitch.” When Baker met the king of Buganda, he appeared in full Highland dress: kilt, sporran and Glengarry bonnet all complete in the heart of Africa.

Alan Moorehead’s seminal account of the hunt for the river’s source, “The White Nile,” was published half a century ago, and, as Mr. Jeal notes, dozens of biographies, including nine of Burton, six of Stanley, three of the Bakers and four of Livingstone have since appeared. Despite the outpouring, Speke had been unfairly overlooked. Thanks to Mr. Jeal, though, he finally achieves his rightful place on the map.