When the Bolshoi’s wunderkinder, Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev, suddenly left the company two years ago, the dance world played endless guessing-games as to where they would end up. It was like Claude Rains in Casablanca: round up the usual suspects. The last company anyone expected, however, was the Mikhailovsky, St Petersburg’s junior company to its senior world-class sister, the Mariinsky.

What drew them? Well, the company has an extraordinary Soviet heritage, playing host to some of the great names of 1930s experimental dance. It probably helps, too, that it is now funded by an oligarch, and, with the appointment of the Spaniard Nacho Duato, he provided that greatest of rarities in Russia, a non-Russian artistic director, who brought with him some of his own choreography and the possibility of a varied repertoire.

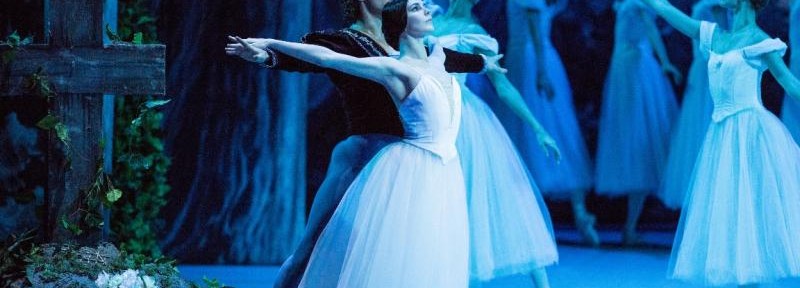

This two-week London season starts more traditionally, with Nikita Dolgushin’s straight-down-the-line production of Giselle. Osipova and Vasiliev were both straitjacketed at the Bolshoi, she guided entirely into soubrette roles, he limited to the gaudy delights of Grigorovich’s Spartacus and other pieces of heroic Soviet posturing. So Giselle is a defiant gesture of the breadth of their ambition.

The evening is Osipova’s (no-one ever staged Giselle because they had a damn fine Albrecht any more than Hamlet is produced because the director has the perfect Gertrude.) Her first act is well thought through, with some lovely moments – when she plays “He loves me, he loves me not” with a daisy, and finds that it comes out to “not”, she steps back, flat-footed, prefiguring her mad scene later. In the mad scene itself, after she chases the invisible something in the air, her arms end crossed in the Wilis’ stance – the ghosts are already calling to her. And her fluttering, spidery hands clutch desperation from the air, even as she automatically bobs a curtsey to Berthe as she passes.

But it is Act II where her performance deepens, from one of fleet technique and carefully considered acting, to mine the real emotional core of this piece. Giselle has survived for so long because it is multi-layered, yet it is too often played flatly: Giselle is a loving girl, she is betrayed, she dies, she returns to rescue her lover. That’s nice, and sweetly sentimental, but it is not Théophile Gautier’s really quite creepy story. In the original, Giselle dies and she returns, but only part of her wants to save her lover; the other part is already a Wili, and it wants to lure her betrayer to his death.

A couple of pieces of overhanging ivy spent much of Act II going up and down like a bride’s nightie

Osipova conveys that dichotomy with eerie ferocity. Her first entry is breathtaking in its virtuosity – rarely have I seen turns of such speed, jumps of such height. Yet it is subordinate to, and in the service of, the drama. When she circles Albrecht, who is not yet aware of her, she is not protecting him, she is marking her territory. The unvarying monotonous perfection of her (enormous) entrechats makes her a puppet of her masters, the Wilis. And as she beckons him, and makes him dance once more, she is loving and caring – and she is carrion, hovering over his doomed body.

Vasiliev was a willing partner, playing an Albrecht of youthful impetuosity and foolishness, rather than of devious betrayal. The Act II partnering could have been smoother, more invisible, but his solos were remarkable yet never broke the spell of the drama to become virtuoso turns, to the detriment of the story.

Myrtha (Ekaterina Borchenko), too, was a steely dramatic foil, and the corps of 24 all they should have been. Olga Semyonova played Bertha with camp vigour, a red-headed Mae West with a riding-crop.

A few bits of clunk will no doubt shortly be ironed out – technical stutters meant a couple of pieces of overhanging ivy spent much of Act II going up and down like a bride’s nightie, and it would be nice if Hilarion (the touching Vladimir Tsal) and Albrecht found somewhere other than Giselle’s grave to abandon their coats and hats: it began to feel like the foyer cloakroom. But on the whole this was a good basic production fronted by two stellar performers.