Two large collages bookend Hannah Höch’s career. First, the cumbersomely titled “Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands” (“Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany”, not on show in this exhibition), a centrifugal spray of creation which made her reputation when it was exhibited at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920; and, half a century later, the grid-like “Lebensbild” (“Life Portrait”, 1972–3). Together they display this astonishing artist’s many preoccupations and her range of approaches.

Born in 1889 into comfortable upper-middle-class circumstances, Höch arrived in Berlin to study at the School of Arts and Crafts, in the feminine disciplines of glass design and embroidery. The good girl soon vanished in Berlin’s post-war ferment, however, as she began a relationship with Raoul Hausmann, then at the centre of the Weimar Dadaists. In the early pieces, one can feel the young artist’s excitement as she drinks in influences – Henri Matisse, Raoul Dufy, then the Fauves, Paul Klee, the Russian Constructivists. Her chosen medium swiftly became collage, and, more specifically, photomontage, as the new print culture made cheap photographs available to recycle into art. Höch’s originality was to take the rhythms and patterns from her applied-arts background, and splice onto it the compulsions and concerns of modernism. “Weiße Form” (“White Form”), in 1919, is underpinned by Constructivist theory, but the forms, which themselves resemble sewing patterns, are laid out in an almost Cubist shape, pressed over a delicate spider-web tracery of embroidery. It was a powerful statement of intent. “I would like”, she wrote, “to blur the firm borders that we human beings, cocksure as we are, are inclined to erect around everything.” And she did.

The same year, “Porträt Gerhard Hauptmann”, a collage depiction of the playwright and Nobel Prize-winner, continued her anatomization, now not merely of art-forms, but of cultural achievement. A famous photograph of the Dada Fair in 1920 showed Raoul Hausmann ready to declaim, with Höch by his side, leaning in submissively, head inclined, shoulders bowed. But it is her collage, not his, that hangs in the background. Her portrait of Gerhard Hauptmann suggests that this gender inequality had long been clear to her: Hauptmann’s head is divided in two, his unsmiling mouth and eyes bracketing another, smiling, female mouth and eyes. “Da-Dandy” shows a man’s profile in red and yellow; inside, his head too is filled with women.

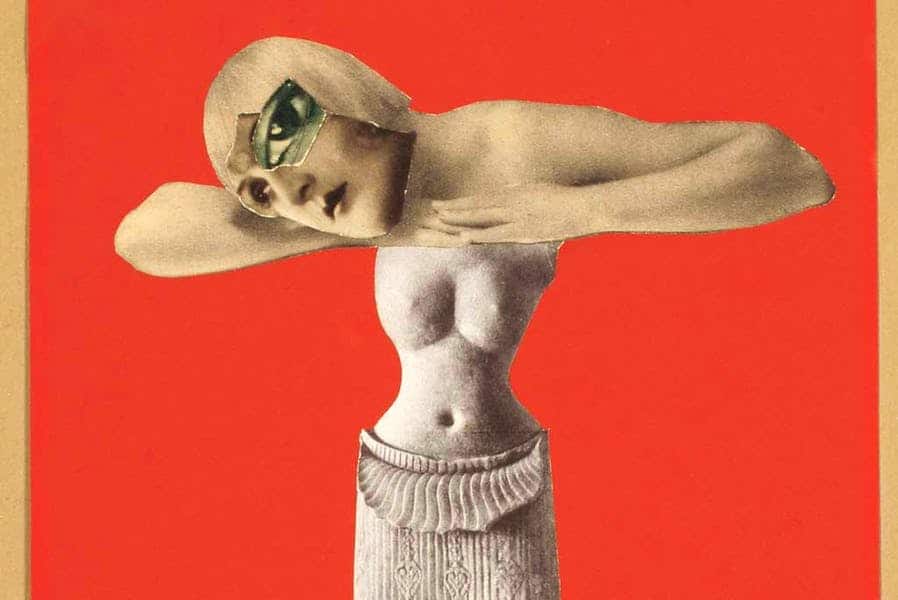

The critic Adolf Behne thought Dada an art of advertisements, photographs, ticket-stubs, “iron crosses, razor blades, cords, braid” and newspaper: pieces of modernity, of masculinity, and of a country emerging from war. It produced, he wrote, an “uncanny suspense”. “Uncanny” in German is unheimlich, un-home-like, unlike-the-place-women-are-supposed-to-be. Höch begged to differ. Women were to the fore again in her series “Aus einem ethnographischen Museum” (“From an ethnographic museum”), where ethnographic elements were conflated with photographs of women from topical magazines, the resulting figures set on plinths, their race and gender displayed for examination by experts. Doing and being done to, self-reflection and self-display, otherness, all are here.

Long before it became an adage, the personal was political for Höch. “Staatshäupter” (“Heads of State”) puts at its centre a photograph of the Weimar Republic’s president, Friedrich Ebert, and its minister of defence, Gustav Noske. These two men, responsible for the brutal suppression of the Spartacist uprising, are here not in formal dress but on the beach, in saggy bathing trunks. Behind them, mockingly cartoonish butterflies, beach balls and a bathing belle cavort, while what may perhaps have been cut from a photograph of a piece of furniture looks like a slightly shocked sea monster staring at a paper sea.

Despite this overt political engagement, Höch has been too frequently dismissed as a woman consumed by “women’s” concerns, photomontaged out of art history. Most accounts of the period omit her entirely, or damn her with patronizing faint praise. Only in the past few decades has her reputation in Germany begun to approach the real merit of her work, and this exhibition is her first in Britain. In part, however, Höch removed herself from the story. In 1926 she began a relationship with a Dutch poet, Til Brugman, later moving to the Hague to be with her. She left the art world once again, in 1936, when she became seriously ill, and again, as the Nazi grip on culture tightened, she left the centre of Berlin for a quiet suburb.

In 1946, however, she re-emerged. She was, she said, “Uninhibited, in the sense of being unburdened”, and her openness to new schools and styles returned unabated, as she returned physically to the materials she had gathered before the war, to her store of clippings, cuttings and patterns. One room at the Whitechapel Gallery is devoted to these albums of images. Ralf Burmeister, head of the archive that holds Höch’s work in Berlin today, queries in his catalogue essay whether these scrapbooks are in fact an achieved work, or simply Höch’s filing system. By giving them their own room, albeit the show’s smallest, the curators have come down on the side of the former. Whether or not this is the case, the bound books can be shown only in limited fashion, and the space could have been better used to show some of Höch’s paintings, none of which figures in this “overview”.

Technology improved colour reproduction, and after the war Höch’s work took on a new visual richness

Technology improved colour reproduction, and after the war Höch’s work took on a new visual richness. The curators and catalogue essayists see, too, an increasing tendency to abstraction, but the world remains ever-present in her work. “Friedenstaube” (“Dove of Peace”), which marked the end of the war, continues her engagement with politics, as barrels of guns turn into letter punches, or perhaps it is vice versa: is she saying information is power, or that power constrains information? The essayists suggest that Höch’s anger is new, but the exhibition as a whole shows that this wonderfully angry woman had long had much to be angry about. No one did, or does, want to know about women and their anger. No one but a woman could – or would – have produced “Der Traum seines Lebens” (“The Dream of His Life”, 1925), a soubrette dressed in frills, bows and flower-bedecked headdress, cut up, cut apart. What is “his dream”? Her face, her legs, her ankles, her breasts.

Towards the end of her life, Höch said, “Plants are simply beautiful. Humans and animals – questionable”. But she went on asking questions. In “Lebensbild”, created when she was well into her eighties, she anatomizes herself as severely as she did others. The eyes, so important in her earlier works, here soften, but the hands come to the fore. A hypnotist’s hands in one of her albums, held to his temples, now move down, to be held judgementally, in front of her, right at the centre of the work; at the top, in the same judicious pose, they cover her eyes; at the bottom, once more, they now hold – a crystal ball?

Hannah Höch may not have had a crystal ball in which to see her terrible century play out. But that this furious, fastidious, feminine artist was there to witness, to record and to report is our great good fortune. That it has taken the best part of a century before she received even a measure of her due is her age’s shame, and ours.

Published in the TLS

2 Comments

Freja Noe Haulrik

May 15, 2017 - 12:40 pmHi! Love the article, however I was wondering, the work Porträt Gerhard Hauptmann, where is this exhibited? I’m asking because I need it for an assignment about the art work.

inspectorbucket

May 15, 2017 - 2:54 pmI’m afraid I don’t know. As you will see from the date of the post, the exhibition was three years ago.