(published in the Telegraph 27 Mar 2012)

The rise and rise of Soho, London’s darkly alluring twilight zone

The rise and rise of Soho, London’s darkly alluring twilight zone

In her fiction, Virginia Woolf transformed Soho into a menacing urban space filled with “fierce” light and “raw” voices, even as she privately commended herself for driving a good bargain on some silk stockings “(flawed slightly)” at Soho’s Berwick Street market.

Soho, a mere 130 acres, with no more than 24,000 residents in the 20th century, is bounded on two sides by the commercial leisure regions of Shaftesbury Avenue and Leicester Square, on the other two by the shopping meccas of Oxford Street and Regent Street. For most of the 19th century it was a ‘“dark, industrial back region that serviced the spectacular front stage of the West End pleasure zone”. In Nights Out, Judith Walkowitz, professor of modern European cultural and social history at Johns Hopkins, explores how, between 1890 and 1939, the industries that thrived on dance, music, food, fashion – and commercial sex – transformed this artisan’s hinterland into a tourist mecca.

At the end of the 19th century the great new thoroughfares of Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue created a twilight zone where the rules didn’t quite apply, an area where to be “foreign” was the norm – only about 4 per cent of Londoners were foreign-born in 1900, whereas a single parish in Soho had nearly 40 per cent foreign-born residents. Yet there was continuity, too: furniture manufacturers in Wardour Street inhabited the same shops that once housed their Regency forebears. Soho thus became both foreign and English, old-fashioned and modern, safe and dangerous.

Virginia Woolf had been in her mid-twenties when an anarchist named Bourdin blew himself up while transporting a bomb to the Greenwich Observatory (Walkowitz, in a very rare slip that indicates she is not a Londoner, calls it the Greenwich conservatory). He soon became renowned as a resident of Soho’s “muddy, inhospitable accumulation of bricks, slates, and stones” – this from Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, which fictionalised Bourdin and spread Soho’s anarchist fame across the world.

Much of Soho was superficially more benign. As Shaftesbury Avenue’s theatres brought audiences out at night, Soho’s “little places” to eat became famous – what one commentator called “London’s escape from English cooking”. Walkowitz contrasts two Italian caterers to great effect, both of them impoverished immigrants from northern Italy. Peppino Leoni opened Quo Vadis on Dean Street in 1940; his politics were proudly fascist, and he was interned during the Second World War. Emidio Recchioni meanwhile pioneered the import of Italian delicacies while using his King Bomba grocery as political cover: imprisoned for his radical views in Italy, from Britain he funded several assassination attempts on Mussolini.

With the war, Free French officers set up unofficial headquarters at the York Minster pub on Dean Street, then informally (now formally) known as the French House; Polish officers, American servicemen and more followed. Meanwhile, British-born Italians were obliged to erect signs like the one Bertorelli had on his eponymous restaurant: “The proprietors are British and have sons serving in the British Army”.

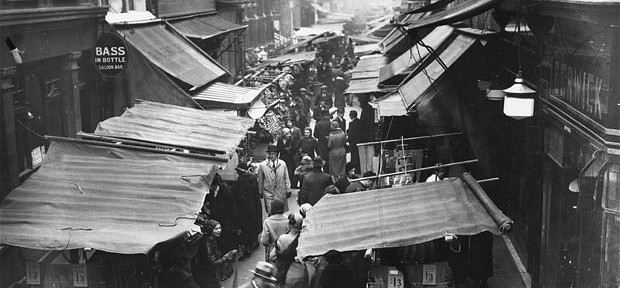

Other trades blossomed in this mêlée. Soho tailors had long been pieceworkers for fashionable West End and Oxford Street shops. By the 1890s, the Berwick Street market was a vibrant retail space: an extension to Oxford Street and also its opposite, with its shopping “area” indistinguishable from the street.

As well as leading the textile trade, the Jews of Soho livened up its more respectable nightlife, which for them centred on the dancehalls and Lyons’ Corner Houses. The Astoria opened in a basement in 1927, and just as foreign food was modified to suit English palates, so daring American and South American dances were anglicised and tamed. Lyons’ specialised in mega-catering: the three Soho Corner Houses seated 9,000 people, and saw up to 15 sittings a day: 135,000 hungry customers, coming to eat, talk, look. And even to cruise: several of the Soho Corner Houses had areas informally allocated to gay customers, with friendly “Nippies” keeping tables for regulars. Other aspects of Soho nightlife were less salubrious, with nightclubs and drinking clubs surviving thanks to illicit, or semi-licit, complicity with the local police.

In the Thirties, as crackdowns on police corruption saw many nightclubs close, Soho seemed ripe for redevelopment, and campaigners feared that the district would become nothing more than a giant car park, “London’s garage”. Thanks to the efforts of the Soho Society and others, that did not come to pass, but the creeping pornification of Soho, which replaced so many other industries, remains only briefly mentioned by the author.

She has, however, a wonderful eye for the telling detail. Soho, she notes, appeared dark and mysterious because, in truth, it was: until the Thirties, the surrounding West End street lights had three times the wattage of Soho’s, making shop and restaurant windows gleam enticingly in the gloom. She also has the ability to conjure a world in a pithy phrase: Romano’s in the Strand was a “clean-shirted Victorian bohemia”. All the more pity, therefore, that much of the book is written in Higher Crit-Speak: “female performers at the Empire publicised iconoclastic bodily idioms that troubled corporeal norms of nation, gender, sexuality and class”.

Walkowitz is famed as the author of City of Dreadful Delight, one of the classic books on 19th-century London nightlife, from child prostitution to Jack the Ripper. Now, in Nights Out, she has produced an engrossing exploration of how a district that was not quite anywhere became a synonym for the multicultural city that is London today.

Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London

Judith R Walkowitz

Yale University Press, £25, 428pp