Richard Hamilton was a relative unknown when in 1956 he produced the collage for which he is still, perhaps, most famous: “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?” (The original is too fragile to travel, and a print version produced by the artist in 1992 takes its place in the Tate’s show.) The piece was included in the Whitechapel Gallery’s seminal This is Tomorrow exhibition, and it would be difficult to claim that the British art establishment ever overlooked him again: the Tate’s current retrospective is its fourth since 1970, and includes some 200 works covering an almost sixty-year career. With two installations from the 50s re-created at the ICA, and fifty prints on show this month at Alan Cristea, this is a useful opportunity to take stock, three years after the artist’s death.

In a world that jostles for firsts, Hamilton has frequently, and plausibly, been put forward as the first Pop artist. “Just what is it . . .” with its rich panoply of consumer objects contains not only the first appearance of the word “Pop” (on the muscleman’s badminton racquet), but also a tin of ham, eight years before Andy Warhol’s soup cans went on show in New York in The American Supermarket exhibition. In a letter around this time, Hamilton defined Pop’s preoccupations, as a school that is: Popular, Transient, Expendable (easily forgotten), Low-cost, Mass-produced, Young, Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous and Big business. Most, apart from “easily forgotten”, can be found in “Just what is it . . .”

And then, over the next five decades, it seems as though the artist set out to test the boundaries of all of those categories in turn. In terms of technique, Hamilton produced installations, oil paintings, prints, drawings, photographic works, computer-manipulated images, industrial design, multiples and collages. He was also one of the early enthusiasts to work substantially in the interstices between techniques, what he called the “marriage of brush and lens” as he painted over photographs, or manipulated layers of mechanical reproductions.

His subject matter, too, was both wide-ranging and unusual. His work adheres to very traditional genres – still lifes, portraits, landscapes, conversation pieces, agitprop and religious subjects – but his most steadfast commitment was to the products of the modern world. In this he was (apart from, in different ways, Warhol) working almost entirely on his own. David Hockney’s subject matter would not have surprised an eighteenth-century artist, allowing for the substitution of river-bathing with swimming pools; Roy Lichtenstein’s would have been (mostly) familiar to the Impressionists. But toasters? Toothbrushes? “Just what is it . . .” included a television, a tape recorder, a vacuum cleaner, a magazine; when Hamilton revisited the idea in 1994, the new print now showed a computer, a microwave and a video-recorder. A 2004 work, “Chiara and Chair”, returned full circle, to 1956’s vacuum cleaner, even as computer-aided perspectival possibilities allowed the artist to take his exploration of the modern interior further.

The two great subjects that spanned Hamilton’s career were consumerism and the industrial world, and space, and how it can be interpreted. “I would like”, he said, “to think of my purpose as a search for what is epic in everyday objects and everyday attitudes.” In this search, he turned initially to James Joyce and Marcel Duchamp. Joyce taught him that he “did not need a style of working”, while from Duchamp he took the idea of the artist not merely as craftsman, but as someone who chooses objects, and by his selection, and scrutiny, turns them into art. A third influence, it seems to me, was Le Corbusier: in Hamilton’s work the “machine for living” appears to be both the artist’s eyes and the screen, whether film, television or, latterly, computer.

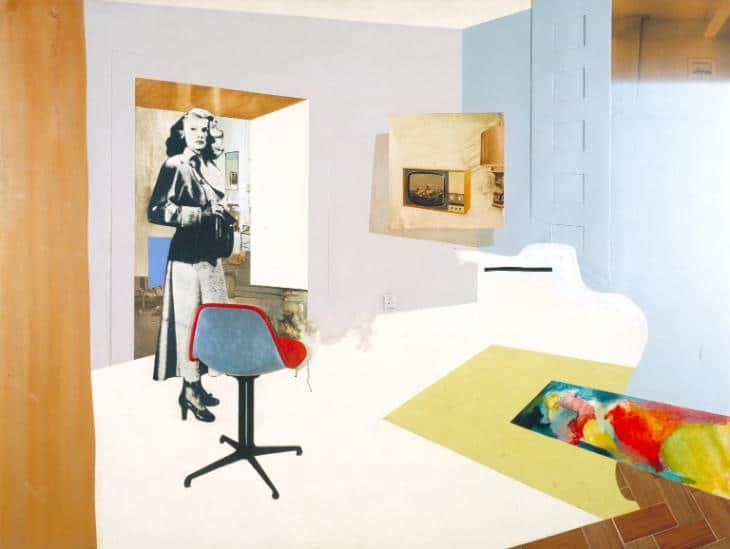

The first big step forward was in the 1960s, when Hamilton moved on from the constricted perspectives of “Just what is it . . .” to a series of interiors, a subject that would continue to provide him with creative impetus until his death in 2011. “Any interior”, he said, “is a set of anachronisms”: the objects that fill our houses, whether purchased or inherited, create layers of time. In the transformation from lived space to artist’s vision, further layers of potential are imposed on the subject.

At this stage, Hamilton worked with photocopies and photographs, cutting and rescaling elements to create perspectival shift, to build mood as well as shape. In “Interiors I” and “II”, and “Desk”, he inserted a cut-out photograph of the B-movie starlet Patricia Knight into an office of terrifying instability: the black, thrusting rectangle that is the side of the desk suddenly wavers; the desktop, at one side solid enough to hold a pencil so realistically reproduced that any nineteenth-century copyist would have been proud, on its other side slithers away into white nothingness; in the second version, the desk itself vanishes, and only its identifiable angular thrust remains: the smile of a deskbound Cheshire Cat.

In the 1990s, computers gave Hamilton the ability to go further, producing two brilliant series, Seven Rooms and Annunciation. In Seven Rooms, Hamilton engaged with the idea of the installation, but reconsidered it for our computer age, to become what might be thought of as non-site-specific-site-specific work. He photographed a series of rooms, and the images were digitally printed onto the gallery walls; this print, complete with gallery wall, was then in turn photographed, and printed onto canvas, some overpainted, some not. Rehung as they are in the Tate, the viewer sees a Russian doll installation in two dimensions. The distancing forces us to examine not merely the life on show, but how lives are lived. These repetitions and reiterations become a way of considering the expressive capabilities of scale, perspective and harmony, in emotional as well as technical terms.

While this is where Hamilton’s significance will, in future, surely be seen to lie, the Tate retrospective reminds us of what a skilled craftsman he was too: an early oil, “Chromatic Grid” (1950), with its swirly pinpoints; or “d’Orientation” (1952), and the Trainsition series, show a lovely delicate colourist in watercolour and gouache.

But this hand-on-canvas work was soon left behind. Hamilton was far more interested in ideas, and these found their expression most often in prints. His 1970 series, Kent State, uses an image from the recent killings at Kent State University, when students protesting against the Vietnam War were shot by the Ohio National Guard. Hamilton selected one image, a student lying paralysed on the ground, replicating it over and over, his heavily mediated framing device never allowing us to forget that the work is not only about a government murdering its citizens, but also about the dissemination of that knowledge.

Hamilton described how he first came across the Kent State image on television, sandwiched between The Black and White Minstrel Show and Match of the Day, and his consequent reluctance to use it: “It was too terrible an incident . . . to submit to arty treatment. Yet there it was in my hand, by chance – I didn’t really choose the subject, it offered itself. It seemed right, too, that art could help to keep the shame in our minds”.

His concern to separate entertainment from an exploration of a state’s abandonment of morality appears to have passed the Tate by. Hamilton elsewhere warned that “Political or moral motivation is hard to handle for an artist”, but so it is too for those who show the art. Here, however, the curators have chosen to display the Kent State pictures across from Swingeing London, Hamilton’s series showing Mick Jagger being arrested for dope smoking, and another series, Fashion-plate, collages of women’s faces taken from fashion photographs. Absent Hamilton’s thoughts on art and morality, the suggestion presented by this hanging is that all three series have some sort of equivalence. (The quotation instead is to be found in the very good Alan Cristea catalogue. The Tate catalogue, hefty even by modern museum standards, has splendid reproductions, but the essays take a lot of space to say remarkably little, while Cristea’s carefully selected quotations from Hamilton himself are consistently enlightening.)

More generally, the Tate’s panels supply minimal information, not even a single biographical outline. That is left to the ICA, which has on show recreations of two installations Hamilton made in the 1950s. There we learn that Hamilton was born in 1922 (although, mysteriously, there is no mention of his death in 2011). As was common for working-class children at the time, Hamilton left school at fourteen, finding employment as an office boy in the advertising department of an electrical engineering firm. He received wartime training in technical drawing, and then worked as a mechanical draughtsman creating templates for tools – that is, making reproductions, the subject that was to consume him.

The ICA’s concise but well-rounded display of his graphic design work shows yet another facet of this protean artist. His typographic skills were not merely comprehensive, but joyous – a poster advertising a Francis Picabia show is an object lesson in how to make grey fun. Alan Cristea Gallery’s selection of fifty prints is similarly astutely pared down, offering an almost flip-book-like ride through six decades.

For Hamilton produced vastly, prodigiously. Often an engagement with new techniques took decades to come to fruition. The late Rooms series is a masterful summation of a lifetime’s work. So, too, are his photographic self-portrait projects, some in the style of Francis Bacon, others tiny Polaroids taken by his friends over a quarter of a century. Other areas are less successful. The Tate has devoted an entire room to what it primly refers to as his “scatological” period (in reality, brightly coloured prints of turds). In retrospect these works appear to be more experiments in new printmaking technology. Similarly, his incursions into politics, whether a portrait of Tony Blair as a gunslinger, or a triptych of reflections on the Troubles, are clearly heartfelt, but their didactic finger-waving brings them perilously close to kitsch.

Hamilton was a trailblazer, and his best work belongs with the very best, a fizzing, dazzling reminder of what a great intelligence brought to post-war art. A pity, then, to dilute it with so many dead ends and false beginnings.

Published in the TLS

RICHARD HAMILTON, Tate Modern

RICHARD HAMILTON AT THE ICA

RICHARD HAMILTON: Word and Image: Prints 1963–2007, Alan Cristea Gallery

Mark Godfrey Paul Schimmel and Vicente Todoli, editors, RICHARD HAMILTON (352pp. Tate. £29.99)

Jonathan Jones, RICHARD HAMILTON: Word and Image: Prints 1963–2007 (155pp. Alan Cristea Gallery. £25)