The Royal Ballet is frequently criticized for playing safe, relying too heavily on its tried-and-trusted crowd-pleasing three-acters. This very mixed bill, therefore, reads as outgoing director Monica Mason’s riposte.

The Royal Ballet is frequently criticized for playing safe, relying too heavily on its tried-and-trusted crowd-pleasing three-acters. This very mixed bill, therefore, reads as outgoing director Monica Mason’s riposte.

In terms of achievement, Christopher Wheeldon’s Polyphonia, returning to Opera House nearly a decade after it was first performed here, takes the laurels. Its homage to Balanchine, and, more particularly, to Agon, was obvious from the start: as Balanchine worked with the then-considered-difficult Stravinsky, so Wheeldon takes Ligeti as his muse; as Balanchine opened with a piece of four-square classicism, so does Wheeldon. Yet while Wheeldon’s Balanchinean ability to create order and space was always visible, what predominates now is a mood of gentleness, especially in the person of Leanne Benjamin, tiny but formidable, imperious but serene, who carves shapes from air.

But the audience was waiting for the two premieres, Sweet Violets by in-house golden boy Liam Scarlett, still in his mid-twenties, and Carbon Life by Wayne McGregor, the company’s resident choreographer.

McGregor, a modern-dance choreographer, has worked with the Royal since 2006, and his style is well-known: hip-popping dislocations, knotted, kinetic partnerings and sky-high hyper-extensions, all frequently set to music that at first hearing seems to have little to do with the lithe goings-on in front. Here it was literally in front, as a roster of headline-grabbing names from the contemporary music scene performed behind the dancers: music by Mark Ronson and Andrew Wyatt, performed by Ronson with Boy George, Hero Fisher, Alison Mosshart and Black Cobain, among others.

All well and good, but the string of songs gives McGregor little to work with as the linear nature of the songs prevents any sense of dramatic development, while Gareth Pugh’s eye-opening costumes – unisex black drawers, S&M-style masks, Holy Week capirotes, finned gauntlets and leggings – are merely a distraction. Many claim that McGregor has created an entirely new dance language. I question, however, how much he has to say in it. In UnDance, created with artist Mark Wallinger crucially acting as dramaturg, his work had a focus that Carbon Life lacks.

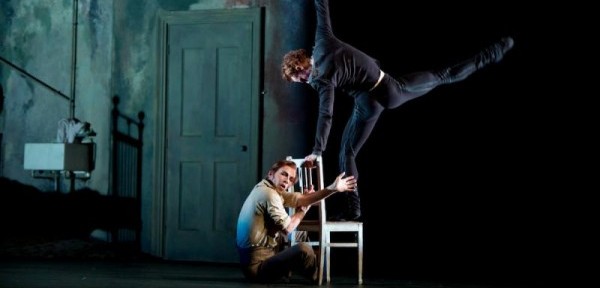

The more interesting debut, Sweet Violets, Scarlett’s first foray into narrative dance-theatre, suffered from the opposite problem: too many ideas, too much to say, all of it tumbling out.

His starting-point is painter Walter Sickert’s rendering of the 1907 murder of Emily Dimmock, a prostitute (Leanne Cope), for which an artist named Robert Wood was tried. Four years ago the Cortauld displayed Sickert’s four paintings and his drawings and prints on the subject, and Sweet Violets captures absolutely their thick, threatening atmosphere.

In Scarlett’s version, Wood (Thiago Soares) is a friend of Sickert (Johan Kobborg), who in turn has been made art-tutor to Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Eddy (Federico Bonelli). While in Sickert’s care the prince marries a prostitute (Laura Morera, in the role of her career), who, after giving birth, is incarcerated in an asylum, while her friend, Mary Jane Kelly (Alina Cojocaru), in reality Jack the Ripper’s last victim, is murdered to preserve the reputation of the royal family.

Scarlett admits in the programme the seriously implausible nature of this story, but onstage his skills nonetheless make this preposterous fluff dramatically compelling: 1888 and 1907 merge in Sickert’s mind, leaving open how much is reality, how much Sickert’s morbid fantasy of past events as the Ripper (Steven McRae at his most unnerving) remains ever-present, the artist’s evil genius.

Scarlett’s dance language in this piece bears a close resemblance to Kenneth MacMillan in Mayerling or Anastasia mode. Yet there is much that is original, too, in the younger choreographer’s movement and ideas, and all is unified by his supremely delicate musical response to Rachmaninoff’s Trio élégiaque. John Macfarlane has produced one of his most nuanced sets, creating (with David Finn’s bravura lighting) a drab, shadowy world where bloody happenings occur in corners, before opening out into a Sickertian music-hall of tarnished glitter, seen from backstage in a splendidly vertiginous coup de théâtre.

It is understandable that a choreographer producing his first narrative work feels the need to explain. Scarlett’s talent is such, however, that he need not. With the unnecessary historical exposition scenes deleted, Sweet Violets will be a desperate, terrifying and exhilarating tour de force.