Van Gogh at Work: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam Marije Vellekoop, with Nienke Bakker; translated by Ted Alkins, Michael Hoyle and Beverley Jackson (304pp. Brussels: Mercatorfonds. £40)

On May Day, thousands of Amsterdammers queued in the spring sunshine as the Van Gogh Museum formally reopened its doors after a seven-month refit, for the kind of invisible but essential works art requires: lighting, humidity-control and so on. What the museum made triumphantly visible, however, was the public face of their eight-year research project into Vincent Van Gogh’s studio practice, both on the walls and in an excellent catalogue. To stress how research, exhibition and publication are a continuous process, the exhibition and publication were all designed, impeccably, by Pièce Montée.

The museum’s first room, and the first pages of the catalogue, set out their stall. The catalogue shows a series of sensually close-up images of nineteenth-century artists’ materials – paints, charcoal, pencils – as well as some of Van Gogh’s surviving sketchbooks, and his palette, loaded with paints and seemingly ready and waiting. The exhibition begins with two self-portraits only a couple of years apart. But while the one from 1886 is a traditionally hued conventional image, the one dated 1888 is in the vivid, slashing palette we know so well.

And that is, in miniature, what the exhibition so ably explores. Van Gogh decided to become an artist aged twenty-seven, after eleven years working for an art dealer and as a teacher/missionary. He painted for a mere ten years, less than half his working life, and his start was unpromising, as the early apprentice copying from “how-to” manuals shows. Watching Van Gogh develop into “Van Gogh” is like one of those speeded-up films of a flower unfolding. In his early years, he studied books, and for a few weeks at a time, here and there, with various teachers – possibly for eight months altogether. His application of what he read and learned, therefore, was idiosyncratic. He read about colour theory, or examined the techniques of painters of the past, but in his early years had to find ways to apply them himself. For example, while many artists used perspective frames, Van Gogh was the only one we know of who physically drew the frame and the threads onto his canvases – there was no one to tell him differently.

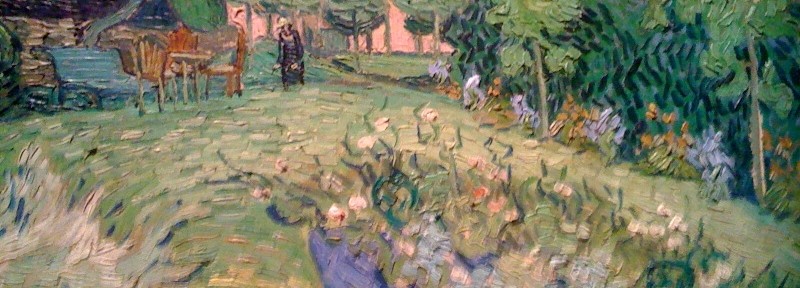

Once in Paris, in 1886, he found friendship and shared working practices with other artists, including Toulouse-Lautrec and Émile Bernard. Here too he tried out different techniques, keeping the elements that worked for him, and discarding the rest. Toulouse-Lautrec was a proponent of peinture à l’essence, using a very thinned paint on unprimed canvas; Signac was at the height of his pointilliste style; Adolphe Monticelli was painting still lives in a heavy, dark impasto. From one Van Gogh took the heightened colours; from the next the staccato, discrete brushstrokes; from the third, the heavy applications of paint and worked surface. From Japanese prints he assimilated cropped compositions, slashing diagonals and broad, flat areas of colour. Later, the simplifications and flat patterns of Paul Gauguin were developed into the stylized, rolling lines and rhythmic patterns that could never be anything but the distinct handwriting of Van Gogh.

And this is the key to the exhibition. This Van Gogh is not the solitary genius, appearing out of nowhere, flourishing in isolation and producing an art that was born fully formed. Instead, through Van Gogh at Work we discover how he studied, and with whom, what his influences were, who were his friends, and how his art developed, as all art does, in conjunction with, as well as in opposition to, ideas of the day. This is backed up not merely by words, but in images: around a quarter of the paintings on display are by Van Gogh’s friends and colleagues, permitting us to see at first hand this artistic give-and-take.

There are also loans from other institutions, chosen and hung to display Van Gogh’s integration into the art world of his day. London’s National Gallery has lent its “Sunflowers”, which now hangs together with the Van Gogh Museum’s own “Sunflowers”, both flanking the Stedelijk Museum’s “La Berceuse (Portrait of Mme Roulin)”, a triptych – the “Sunflowers” “like candles” lighting the centrepiece, the artist wrote – planned as a gift to Gauguin.

The catalogue and the exhibition both stress, too, how the extraordinary nature of many of Van Gogh’s works would have been less extraordinary at the time. Van Gogh was using new synthetic colours, which had been developed only in the previous few decades. Because of his colour choices, many of his works have altered in ways we are no longer aware of. “Gauguin’s Chair” now has a blue background; when it was painted, it was purple.

A self-portrait of 1887 was photographed in 1903. Even in the black-and-white photograph, it is clear how the cochineal then linked colours and brushstrokes that, as the colour has faded to merely pink, now stand starkly separate.

For colour is, of course, at the core of Van Gogh’s work. He began to read about complementary colours in 1884, only four years into his studies. Being able to use a dark colour for something light, as long as the colours around it were darker still, he realized, gave the artist true freedom, leaving “the painter free to seek colours that form a whole. . . COLOUR EXPRESSES SOMETHING IN ITSELF”, he wrote with wonder. And at the end of his life, in 1890 in Auvers, in “Wheatfield with Crows” he made the contrasts of blue sky, with its pure and broken hues, the yellow-orange of wheat surrounding a red path lined with green (today the red has turned brown), into an expression of reality, not a replication of reality. In 1888, he wrote, “the painter of the future [will be] a colourist such as there hasn’t been before”. What he didn’t realize then, in fact never knew, was that he was that colourist.

The Van Gogh Museum, however, knows it, and allows us to relearn it too, in a hang that is triumphant, not merely for allowing a popular artist to shine out once more, but for reminding us, in a measured, thoughtful and intelligent manner, what museums, and what scholarship, are for.

For those who cannot get to Amsterdam, and for whom the catalogue is out of reach, the museum plans to produce apps, the first of which, covering some of the letters, is already available for download. A second, which allows viewers to leaf through the sketchbooks page by page, will follow shortly. For those who can’t wait, the Folio Society has produced a facsimile of the four surviving sketchbooks in the Van Gogh Museum, for a mere £445.

—TLS, 7 June 2013