The artist Howard Hodgkin has been collecting Indian art since he was at Eton. For some years now his collection has been on loan to the Ashmolean, and a rotating selection of pictures from it are frequently on display. Yet to see all 100-plus works together is a revelation, as viewers get a sense not only of the collection, but also an insight into the collector’s personality: what speaks to him.

The artist Howard Hodgkin has been collecting Indian art since he was at Eton. For some years now his collection has been on loan to the Ashmolean, and a rotating selection of pictures from it are frequently on display. Yet to see all 100-plus works together is a revelation, as viewers get a sense not only of the collection, but also an insight into the collector’s personality: what speaks to him.

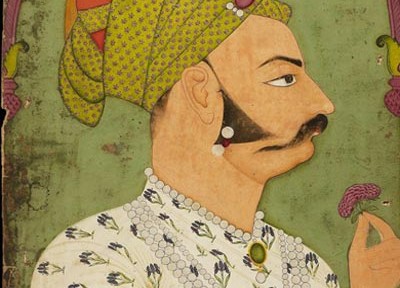

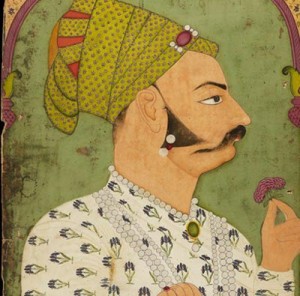

Miniatures from the Mughal empire often depict tiny, enclosed spaces, with figures delicately placed among painstakingly reproduced textiles and carefully detailed flora and fauna, the layers of pattern deftly weaving themselves into magically perfect worlds. Hodgkin is drawn to these depictions of what he calls “a whole world”, one that’s both “completely convincing” and “completely separate” from Western tradition. But Hodgkin also appears attracted to more open compositions, to works that integrate the white paper as an element in the image.

He obviously also has a passion for elephants, perhaps because they too are most often displayed against flat coloured backgrounds – though the animals’ combination of majesty and charm as painted by these Indian masters would beguile anyone. However minimal the composition, the personalities of these royal beasts shine through. One even appears to have his eye slyly on the viewer, almost smiling with shy pride at the splendour of his flowered saddle-cloth.

Other works head towards abstraction: Sultan Ali Adil Shah II hunting a tiger (1660) shows a gloriously gold-gowned bowman taking aim, but the eye focuses more on the elaborate textile folds and greyed-out background than on the action, the tiger merely snarling quietly at the edge of the page.

Some are quirky curiosities, such as Maharaja Balwant Singh and a goose, a drawing of a courtyard flattened out schematically, like a blueprint, while in the centre, staring solemnly at each other, are a goose and a man, the latter a stark black-pencilled silhouette adorned with a pair of pink shoes. What is this a picture of? An omen, a dream, a legend? Or just the ultimate odd couple?

As well as these works from the major artistic centres of Mughal art, there are also a number of pictures from smaller Rajput courts. Particularly beautiful are the tiny works created to illustrate the subjects of musical modes, or ragas (currently the subject of a smaller, less refined show at Dulwich Picture Gallery) .

While it’s easy to find analogies with Western art, the uniqueness of these works always fights back. The colour-world, for one, is inconceivable in the West before the 20th century, filled as it is with hot pinks, dazzling oranges and acid blues that make even the Fauves look tame.

Bright colours do not necessarily signify a cheerful world, though. Bhadrakali, the Destroyer of the Universe, is a blue-skinned four-armed goddess who literally consumes the dead, and here the intense colours highlight Kali’s power as she defies both time and death.

And that, of course, is what great art does: it defies time and death. In the end, the labels “Western” and “Eastern” do not matter. As these two shows allow us to discover, a “shot to the heart” is there for anyone who has the will to look, and the desire to learn.

The world of Mughal enclosures, diamond-bright and bejewelled, could not be further away from our own; and yet, like the goddess Kali, the art it produced devours time and space, defying the centuries to continue to move move us today.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, to Apr 22; www.ashmolean.org

This review also appears in SEVEN magazine, free with the Sunday Telegraph