The actor-biographer Simon Callow has played Dickens, and has created Dickensian characters, in monologues and in a solo bravura rendition of A Christmas Carol. Now he suggests that the theatricality of Dickens’s own life is a subject worthy of exploration in book form.

So it is, and if Callow had done so, it might have made a useful addition to what he rightly identifies as the ‘tsuanami’ of books that are appearing for Dickens’ bicentennial. But in this cursory biography, he merely makes token gestures in that direction: we learn rather a lot about Charles Mathews’ one-man shows; and Callow describes the theatrical impulses behind some of the novels. But mostly he follows the well-worn biographical path — of Dickens’s unhappy childhood, when his feckless father was imprisoned for debt and he was sent to work in a blacking-factory; followed by the lower-middle-class boy becoming, through sheer effort of will, a journalist, then a sketchwriter, then a dizzyingly successful novelist; next the unhappy marriage and secret mistress, before he reached new audiences as a performer-reader of his own material.

Callow appears to have written at warp-speed, paying little attention to his prose, substituting lists of adjectives for characterisation. Dickens is ‘vivacious, charismatic, compassionate, dark, dazzling, generous, destructive, sentimental’; a dozen pages later, he is ‘vivacious, imaginative, amusing, dreamy, affectionate’. Before that, he was born ‘in a small but pleasant, newly built’ house, and later lived in another ‘nice’ one.

‘Nice’ is a favourite word; and a Niagara of clichés pours over these pages. When Dickens’s first love, Maria Beadnell, rejected him, ‘He had given everything of himself. He had lowered his guard, bared his heart. And she had just toyed with him.’ He lacks only a moustache to twiddle.

Callow is also fairly cavalier when it comes to who did what when. He repeats old myths that have long been rejected, and gives actions and thoughts that are nowhere available to us (‘Dickens gasped’, for instance). The book is devoid of historical context, describing as ‘odd’ things that were commonplace at the time (the Dickens’s quiet marriage, or the sister-in-law living with the newly married couple). We are informed that Dickens lived in a world without ‘telephones, telegrams, tape-recorders or television’ — so recreating a vanished world is clearly not on Callow’s agenda.

Instead, what Dickens wrote as an adult is assumed to be the reality lived by him as a child. He is given remarkably little credit for imagination. To assume David Copperfield’s childhood to be a precise replica of Dickens’s own is alarmingly facile.

Callow sees Dickens through a prism of historical inevitability: he is now regarded as the great novelist of the 19th century, and therefore everything in his lifestory must lead towards that point. Far more interesting is Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s view. Becoming Dickens is everything Callow’s book is not: brilliantly original, stylishly written, thoughtful, measured and altogether exhilarating.

He begins by reminding us that novels are word-machines ‘designed to help us look differently at the world’. Concentrating on Dickens in his twenties, when he was growing to be the writer we think we know, Douglas-Fairhurst shows us what might have been by examining the careers Dickens tried and rejected: the lawyer’s clerk, the shorthand writer, the journalist, the hopeful actor, playwright, theatrical impresario, even the potential emigrant to the West Indies. This matters, because, Dickens wrote: ‘These things have made me what I am.’ So too, of course, did his childhood trauma, his failed love-affair with Maria Beadnell, his initially happy marriage, and the death of his sister-in-law, for which he seemed to begrudge his wife and her parents their grieving.

Inventing stories is a way of making sense of a world that seems cruel, or merely indifferent, by taking for oneself the lead part in a drama and creating a coherent narrative out of random events. And yet, even while Dickens was constructing that alternate reality, he, like everyone else, lived in a world of dead-ends and might-have-beens. It is Douglas-Fairhurst’s triumph that he helps us understand how the textures of 19th-century life generally, and Dickens’s life in particular, were reformulated into works of art that continue to resonate two centuries later.

Becoming Dickens is itself a work of art. Incidents that have been written about hundreds of times before are made fresh: when Dickens’s father was arrested for debt, ‘the family had to face up to the fact that the luxuries they could no longer afford included the young Charles’s childhood’. Callow gives us several pages on Charles Mathews, and we’re not quite sure why. Douglas-Fairhurst is far more succinct, yet throws new light on Dickens’s fascination with Mathews’s monologues, which showed ‘that person al identity was largely a matter of self-identity’, a crucial lesson to this self-inventor. Throughout, we are given just the right amount of historical background, so that we understand the context Dickens was operating in without being overwhelmed by unnecessary detail.

al identity was largely a matter of self-identity’, a crucial lesson to this self-inventor. Throughout, we are given just the right amount of historical background, so that we understand the context Dickens was operating in without being overwhelmed by unnecessary detail.

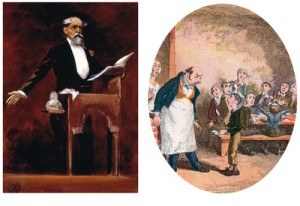

But, ultimately, it is the keen psychological insights that make Douglas-Fairhurst’s book so rewarding. It was, he shows us, Dickens’s identification with children who hunger not just for food, but for love, for acceptance, and for security, that make it not at all coincidental that his most famous line was, ‘Please, sir, I want some more.’