The technical term for Ratmansky’s 2003 The Bright Stream, now in repertory at American Ballet Theater, is a ‘romp’.

That this piece can charm is a miracle itself: the 1935 original, with music by Shostakovich, a libretto by Adrian Piotrovsky and choreography by Fyodor Lopukhov, was condemned by Stalin. Piotrovsky died in the Gulag; Lopukhov was fired from the directorship of the Bolshoi and ended his days choreographing for children; Shostakovich never wrote for the theatre again. The ballet is a comedy set on a collective farm, soon after, we now know, Stalin’s engineered famine killed perhaps 10 million people. Yet Ratmansky heard Gennady Rozhdestvensky’s 1980s recording and, identifying its mix of beauty and sheer rumpty-tump danceability – ‘like Minkus, but on the level of Shostakovich’s genius’ – he created a new ballet to Lopukhov’s scenario.

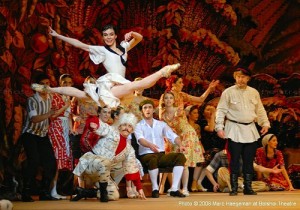

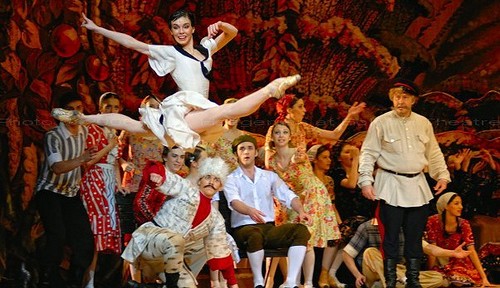

Zina (Julie Kent), a farm-worker, recognizes among a group of travelling performers her former colleague, a ballerina (Isabella Boylston), even as Zina’s husband Pyotr (Ivan Vasiliev) falls for the sophisticated visitor from the city. Discovering this, the women make plans to trick him, Zina dressing up as the ballerina’s partner, while he (Johan Kobborg) in turn is forced, protesting, into the ballerina’s sylph costume.

In a typical reversal on classical style, Ratmansky gives us a first act full of divertissements, as the farmworkers and their visitors celebrate the harvest; only in the second does the plot get moving, as various men mooning after unavailable women are taught their lesson, including a lecherous accordion-player, who is prevented from seducing a schoolgirl by a tractor-driver disguised as a dog (oh, not that old plot, you cry!).

On repeated viewings, sometimes the stream does not run as brightly as it might, but Julie Kent gives Zina a quiet charm interspersed with tight, bright footwork (which contrasts oddly against the younger, less experienced Boylston, who, as the ballerina, is supposed to patronize her – those jokes fell a little flat). A bigger – or at least splashier – pleasure is Ivan Vasiliev, the ex-Bolshoi firecracker, who gives Pyotr a series of staggering jumps, as well as a charm that easily makes Zina’s continuing love for him comprehensible. A gloriously funny Johan Kobborg, once dressed as the ballerina, is alternately camp and hangdog, fleet and flatfooted, but always remains on course, demurely stealing the show from under the noses of his younger and flashier colleagues.

Ultimately, The Bright Stream is about friendship, and ABT, too often seen as a company where superstars jet in to do their turns in front of a compliant corps de ballet, in this piece becomes a place of equals, artists sharing their joy in dance.

Across the plaza, another paean to friendship is on display, as New York City Ballet revives Fancy Free, Jerome Robbins’ story of three sailors on shore-leave. Robbins’ mix of Broadway vernacular presentation and classical-dance vocabulary continues to charm, even as the men’s behaviour, in 1944 so comic, today seems to be a menacing form of harassment as they pursue every woman who crosses their paths. Andrew Veyette and Robert Fairchild strike the right all-American note, but it is Daniel Ulbricht in the ‘short friend’ role who carves more interesting shapes out of the air, shading and colouring his steps to a higher level.

No one comes out with much dignity from Peter Martins’ Jeu de Cartes, to Stravinsky. Originally created in 1992 as a leotard ballet, it has had the misfortune to be redesigned (by Ian Falconer): the corps are in white, with the card suits on their chests, but the principals are dressed as court cards, right down to mix-‘n’-match legs, one solid, one striped, or, for poor Tiler Peck as the female lead, red tights and shoes. Stravinsky’s music is, unusually, not particularly danceable – Balanchine’s attempt at the same piece was a rare miss for him, and Martins frequently has to double back choreographically and repeat and invert steps solely to fill the requisite number of bars. Yet the corps groupings, in particular, are attractive, even if the dance does not entirely capture the music’s urgent drive.

Another odd mixture is Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky Suite No. 3. Balanchine created his brilliantly virtuosic and formally classical Theme and Variations to the last movement of this orchestral suite in 1947; nearly a quarter of a century later he went back to it, adding the first three movements in Romantic style. The first three movements take place behind a scrim, in a stereotypically Romantic haze, with the women barefoot or in soft slippers, with long skirts, their hair down; in the fourth movement the scrim rises to reveal more clearly a colonnade and chandeliers as the company appears in classical tutus (virulent turquoise for the girls – as viciously unflattering as those in Jeu de Cartes).

The first sections are scenes of unfulfilled Romantic love and longing; the last is the resolution brought about by classical rigour and harmony. In the ‘Élégie’, Teresa Reichlen is an extraordinary visionary, ecstatic and nubile by turns, her tiny head and long body bending vertiginously backwards as the music and desire fills her. In the ‘Theme and Variations’ Ashley Bouder should bring the evening to a triumphant close, but her high-held head gazing up and out, past the audience, and her flat, unarticulated upper body, render prosaic what should have been a final dramatic sweep.

No one can claim that drama is missing back at ABT with their rip-roaring, scenery-chewing, forehead-clutching Onegin. Cranko’s rather creaky 1960s piece is right up their street, giving their two Russian stars (Diana Vishneva as Tatiana, Natalia Osipova as Olga) plenty of scope.

Cranko, unlike Ratmansky, seems not to have been particularly motivated by the music, which is not from Tchaikovsky’s opera, but is instead assembled from a range of the composer’s works. These were then orchestrated and shaped by Kurt-Heinz Stolze to ensure that each scene is brought, unsubtly and with metronomic regularity, crashing to a finale.

The raison-d’être of the evening, however, is the dancers. Marcelo Gomes, usually a joyous, even friendly, presence, is constricted by the role’s requirement for Byronic brooding, and is unable to do much with his material until the letter scene. As ballet has not got the grammatical syntax to unroll future or past tense plot elements, the scene in which Tatiana writes of her feelings to Onegin becomes a dream, no longer showing Tatiana’s desires, but Onegin’s response – actuality rather than expectation. But Gomes takes the half-chance he is given, and makes Onegin’s behaviour almost forgivable.

His Tatiana, Vishneva, fills every step, no matter how banal, with meaning. She thinks Onegin is offering her his hand; instead, he shoots his cuff and she is left, her own hand outstretched, adrift; it is a little masterpiece of a moment, created by Vishneva out of nothing. Her pas de deux with her husband (a splendid Gennadi Saveliev) is a rare thing in dance, an expression of mature, contented love. Elsewhere, Vishneva is well matched by Natalia Osipova, her opposite physically as well as emotionally. As Vishneva is built on tragedy-queen lines, all gaunt, broken wrists and sadly drooping head, so perky little Osipova, with her chubby, rounded arms, is all girlish charm and bounce. The two together are the cast of dreams.