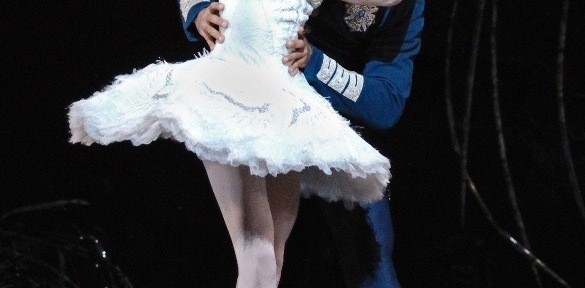

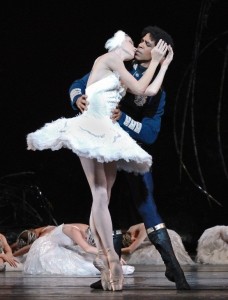

The Royal Ballet’s autumn season began on Monday, but this was the eagerly awaited Swan Lake. Natalia Osipova, ex-Bolshoi, now principal with American Ballet Theater and the Mikhailovsky in St Petersburg, was making her debut as a guest with the Royal Ballet, partnered by Carlos Acosta.

The Royal Ballet’s autumn season began on Monday, but this was the eagerly awaited Swan Lake. Natalia Osipova, ex-Bolshoi, now principal with American Ballet Theater and the Mikhailovsky in St Petersburg, was making her debut as a guest with the Royal Ballet, partnered by Carlos Acosta.

Osipova had, dramatically, left the Bolshoi for the smaller and less prestigious Mikhailovsky, to the puzzlement of many. But the Bolshoi streams its dancers: a certain type is classical, another is romantic, another – Osipova’s type – play soubrettes. Her Kitri in Don Quixote (first seen in London in 2007) propelled her into the starriest leagues, but at the Bolshoi that didn’t necessarily mean she had a crack at any role she chose. At ABT she has been dancing Giselle, Romeo and Juliet and Sleeping Beauty; now on to Swan Lake.

The Royal’s production of Swan Lake, produced by Anthony Dowell nearly a quarter of a century ago, is looking more than its age. It has become a pantomime dame of ballets, its two court acts filled with sound, and fury, and signifying nothing. The two white acts, despite Yolanda Sonnabend’s tragic muse swan costumes, continues serenely pure, especially Act IV, with its music restored under the direction of Tchaikovsky scholar Roland John Wiley.

But to the star, which was all anyone was interested in this evening. Osipova is now 26, and she is growing in stature with every role. Tragedy is not yet in her bones – her charmingly uptilted nose, gamine stature and rounded features fight her every step of the way – but she has learnt to use her plush, lush, deep bends to convey sorrow as well as sensuality. In Act II, the “white swan” act, she is still feeling her way. The great white pas de deux is not yet a coherent whole – there are good moments, and then moments when her laser-focus fades somewhat. But the good is very good indeed, and her attention to detail and depth of emotional involvement is tremendous.

Act III, the “black swan” Odile, is more natural territory, with its ferocious technical demands, which Osipova met with almost insolent ease – pirouettes were substituted for half the fouettés, as though it were a mere bagatelle. Occasionally the interpretation tipped over from as yet undeveloped to excessively broad – the moment that, as Odile, she parodied a droopy Odette was an unattractive invention that one hopes will never reappear.

But it will be the small details that linger – the floating bourrées with which she ended Act II, the moment of emotional release when she leant back against her prince before, her swan maidens catching her eye, she pulled away, a dutiful princess once more.

Carlos Acosta, a fine partner, looked a tad dutiful himself, rarely seeming to become emotionally invested, although Osipova’s fouettés did seem to spur him to match her turn for turn. Otherwise, it is hard for anyone to make much of a mark on this hodgepodge. Hikaru Kobayashi found the right Degas-like shapes for the Act I pas de trois, and Dawid Trzensimiech showed his beautiful carriage and stylish feet.

The evening, however, was Osipova’s. Deservedly.